What is a non-native species?

The term native is used to refer to any species, both plant and animal, that has made its way to the UK naturally and not introduced by humans, either intentionally or accidentally. After the last ice age and before the UK was disconnected from mainland Europe, more habitable conditions allowed trees and plants to become established, these colonised species are what we now recognise as our native flora. Since then most new species have been brought to the UK by humans, which are known as non-native.

When a non-native species is introduced into a new ecosystem, it may survive in small, discrete populations or it may not be able to become established outside of its natural range and will ultimately die out. Only a small proportion of non-native species go on to cause problems and become invasive. This group of species that have been introduced to the UK through human intervention and which pose a serious threat to our native flora and fauna, are known as Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS).

Why are Invasive Non-Native Species damaging?

INNS cause significant ecological and financial damage and are estimated to cost the British economy £1.7 billion a year in trying to tackle the problem, which does not include less quantifiable costs to ecosystem functions and biodiversity. The introduction of INNS is recognised as one of the major causes of biodiversity loss both in the UK and worldwide.

With increased human trade and tourism, INNS can come from all over the world but in terms of plants, they are often brought into the UK through the aquaculture trade or as ornamental plants for gardens. There are around 50 species on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, the legislation states that ‘it is illegal to plant or otherwise cause to grow in the wild any plant listed in Schedule 9 to the Act’.

What is the project hoping to achieve?

The River Frome catchment is currently failing to achieve good ecological status due in part to rural land use and riparian habitat degradation. A project called the ‘River Frome Invasives Control Initiative’ aims to improve river habitats through a targeted control programme of removing invasive species, restoring fish habitats and improving eel passage over minor barriers throughout the catchment. Funding for this project has come from the Environment Agency. The Water Environment Grant (WEG) scheme provides funding to improve the water environment in rural England.

The removal of stands of invasive Himalayan Balsam and the eradication of injurious giant hogweed (by stem injection) along the Painswick Stream will improve the diversity and connectivity of native marginal vegetation along this waterbody, therefore improving habitat for the benefit of our native plants and animals.

What is Himalayan Balsam and where does it grow?

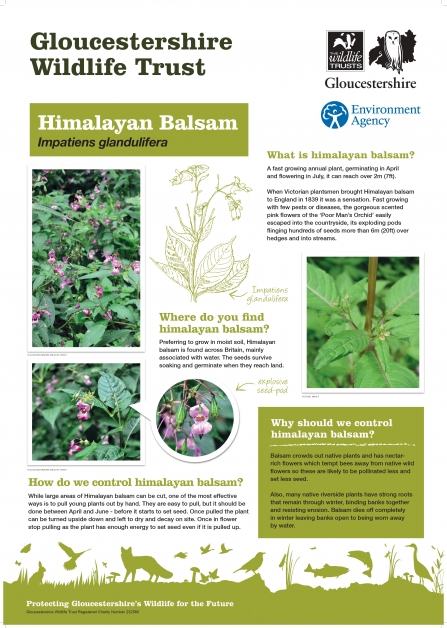

A fast growing annual plant, germinating in April and flowering in July, it can reach over 2m (7ft). When Victorian plantsmen brought Himalayan Balsam to England in 1839 it was a sensation. Fast growing with few pests or diseases, the gorgeous scented pink flowers of the ‘Poor Man’s Orchid’ easily escaped into the countryside, its exploding pods firing hundreds of seeds more than 6m (20ft) into rivers and streams.

Himalayan Balsam is found across Britain and prefers moist ground conditions, often found growing in swathes along the banks of rivers or streams. The seeds survive soaking and germinate when they reach land. Along the Painswick Stream banks are dominated by Himalayan Balsam that allow very little elsewhere the chance to flourish.

Why should we control Himalayan Balam?

Once Himalayan balsam has taken a hold it forms dense stands, which crowds out native plants from growing. Furthermore, it has nectar rich flowers which tempt bees away from native wild flowers, so these are less likely to be pollinated and set less seed.

Many native riverside plants have strong roots that remain through winter, binding banks together and resisting erosion. In contrast, Himalayan Balsam dies off completely in winter leaving banks open to being worn away by water.

INNS not only out compete our native flora for nutrients, space and light but can also change the rates of nutrient cycling in aquatic habitats that can alter the amount of oxygen available in the water. This can be particularly damaging to our native plants and animals.

What can be done to help prevent the spread of Invasive Non-Native Species?

Prevention is key when it comes to tackling INNS but if that fails then acting quickly to prevent a problematic species becoming established is equally important. Where INNS are present, a control and/or eradication programme should be considered.

With cooperation from willing landowners, suitable resources and dedicated people a significant effort can be made to help our rare and native plants and animals. While large areas of Himalayan Balsam can be cut, one of the most effective ways to control its spread is to pull young plants out by hand. They are easy to pull but it should be done between April and June, before it starts to set seed. Once pulled the plant can be turned upside down and left to dry and decay on site.

Below are some ways that you can help to stop the spread of INNS:

- Take part in local volunteer work parties, run by Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust in the Painswick Valley, to help control Himalayan Balsam.

- Inform others about INNS to help spread public awareness, so that others are better informed and educated about INNS to help prevent problems arising in the first place but also to help control and eradicate problem species.

- Try to use plant native species in your garden and do not plant any species that are listed on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, as these species are illegal to plant or help grow.

- Dispose of garden waste appropriately. Best practice is to compost responsibly or use a local garden waste rubbish collection.

- Do not dispose of unwanted or problem plants by leaving them in the countryside or give them away to friends.

- When moving from one watercourse to another, remember to clean your footwear or any equipment that has been in the water, such as fishing equipment, kayaks, boats etc. as small amounts of an INNS can cause an invasion in another waterbody.

- Never throw any garden or aquarium plants into the wild. Similarly, don’t put them into your normal waste bin, tip them down land drains or dump them in the countryside.

- The GB Non Native Species Secretariat website provides advice on managing invasive species and has guidance on what to do if you see any INNS.